The new Ghost Rider movie prompted me to begin this series on the history of horror comics. (My distinguished colleague Barry Pearl points out that Ghost Rider is not exactly a horror comic. True: Skull-head is more of a supernatural superhero, at the crossroads of the superhero and horror genres. But I still see the series as riding the horror trend of the early 70s, a topic I’ll take up later in this series. Anyway, that’s why I’m writing about horror comics in February. Halloween comes early around here.) In this installment I’ll set the background for the rise of horror comics by looking at the predecessors of the genre in literature, film, and radio. (One other important predecessor I’ll mention but won’t cover here is pulp magazine horror, which I’ll take up separately another time.)

Supernatural Horror in Literature

Horror comics drew from a Gothic horror tradition dating back to the 18th century. H.P. Lovecraft’s definitive essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature” traces the descent of Gothic horror from Horace Walpole’s 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto. Walpole’s tale introduced now-familiar conventions such as a haunted castle, a maiden in distress, a villain to menace her, a prince in waiting to rescue her, and a rationalistic ending to explain away the supernatural mystery. (This last element has been named “The Scooby Doo Ending” by my friend Dr. Robert Stock, author of the encyclopedic horror literature review The Flutes of Dionysus, which I recommend for more detailed treatment of literary horror.) Walpole’s story would appear 184 years later in the first issue of Adventures into the Unknown, the first ongoing horror comic.

Stalking the Stage

Walpole’s popularity spawned a slew of successors, and by the early 19th century, Gothic horror had grown popular enough to be satirized by Jane Austen and to make its way from page to stage. The spark was an 1816 literary gathering in Switzerland that engendered both Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the predecessor of Dracula. The latter was an 1819 short story called The Vampyre that was inspired by the Shelleys’ friend Lord Byron but was actually written by another member of their literary circle, John Polidori. Polidori’s work was publicized with attribution to Byron, and critics as esteemed as Goethe praised it as Byron’s best work, despite denials from both Byron and Polidori.

Within a year of Polidori’s publication, the Paris theater was running three different vampire plays. By 1823, Frankenstein had also been adapted as a play. In 1826 Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau recorded that during his travels in London, he attended a double bill of Frankenstein followed by The Vampyre.

Over the next hundred years, other popular monsters began stalking the stage. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, published in 1886, was adapted as a play the next year. Bram Stoker’s Dracula received its first authorized adaptation in England in 1924 and came to Broadway in 1927, introducing American audiences to Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi.

From Stage to Screen

By this time, horror had invaded the silent screen. The first known silent horror movie was a 1908 adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by the Selig Polyscope Company. This was followed up over the next decade by silent adaptations of classic horror authors such as Poe, Shelley, and E.T.A. Hoffmann. During the 1920s Lon Chaney’s brilliant work brought the genre to widespread popularity. By 1931 Jekyll alone had been adapted to silent film no less than seven times.

When Monsters Began to Talk

1931 saw the dawn of the horror talkie. Universal Studios set the stage with an adaptation of Lugosi’s popular Broadway version of Dracula, which premiered in New York City at the Roxy Theater on February 12, 1931. (Apparently I’m not the only one who thinks of horror movies around Valentine’s Day.) The 1931 Christmas season capitalized on the Count’s success by following up with Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein for Universal on December 4 and Fredric March’s rendition of Jekyll for Paramount on New Year’s Eve. A wave of classic horror films and sequels continued to surge for the next five years, peaking with Bride of Frankenstein in 1935 and crashing out with Dracula’s Daughter in 1936.

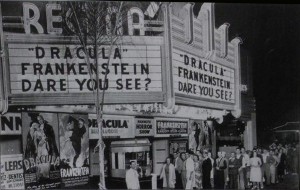

A second wave began gathering on August 5, 1938, when Los Angeles’ floundering Regina Theater tried a desperate ploy to stave off bankruptcy by releasing a four-day double-bill re-release of Dracula and Frankenstein. Crowds began flooding the theater, to be greeted by live appearances from Bela Lugosi. Universal took notice of Regina’s successful revival of the Frankenstein-vampire formula and began releasing the double-bill around the country.

The combination of the Count and the Creature broke box office records, inspiring a new series of sequels to Universal’s classic horror films. Soon Dracula and Frankenstein were meeting each other, the Wolf Man, and ultimately, Abbott and Costello. The release of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein in 1948 marked the descent of the genre into self-parody and the end of the second Universal horror wave.

Meanwhile RKO rode the wave, giving the horror genre a film noir cast under the guidance of producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur. In 1942 Lewton produced Cat People, a moody, psychoanalytical twist on the lycanthropy film genre. Released twelve months after Universal’s successful The Wolf Man, the film proved RKO’s biggest box office success of 1942. Lewton went on to produce seven similar films for the studio between 1943 and 1946, ranging over subjects such as zombies, cults, ghosts, grave robbers, live burials, and insane asylums, and reviving the career of Boris Karloff in the process.

The Creaking Door: Horror on the Radio

The success of Hollywood horror spilled over onto the radio. The first horror radio show was The Witch’s Tale, which aired on WOR and Mutual and in syndication, running from 1931 to 1938. The stories were hosted by an old witch named Nancy, who echoed the sinister chuckling narrative style of the Shadow, and inspired the later EC character the Old Witch. The series began in May 1931 three months after the film release of Dracula, and it included an adaptation of Frankenstein, which aired August 3, 1931, four months ahead of the film.

Nancy and the Shadow inspired a host of radio horror and mystery narrators with a dark sense of humor. The zenith of the genre was The Inner Sanctum, which ran from January 1941 to October 1952, moving between ABC and CBS several times over the course of 526 episodes. The show was produced by Himan Brown, who would later revive it in the form of the CBS Radio Mystery Theater in 1974. Himan gave the show a superior production quality that drew stars like Boris Karloff, Claude Rains, Everett Sloane, Peter Lorre, Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, Lionel Barrymore, Mary Astor, Richard Widmark, and Agnes Moorhead, among others.

Inner Sanctum episodes were introduced to the tune of a creaking door, which became the show’s trademark. Episodes were hosted initially by Raymond Edward Johnson and later by Paul McGrath, who played a creepy host telling puns bad enough to wake the dead. For instance, the Host once announced, “I used to date a vampire, but we had to break up. It turned out I wasn’t her. . .blood type.”

Such macabre musings were paired for laughs opposite straight-laced representatives for advertising products, notably Mary Bennett for Lipton Tea. Bennett cringed from the Host’s awful puns and chided his twisted sense of humor, especially when it didn’t display proper reverence for Lipton products. During one episode, she took exception to the Host’s suggestion that if he started choking, she could revive him with Lipton Tea. “Must I work with the only person who doesn’t know the proper use of Lipton Tea?” Bennett complained to the audience. “Oh, Mary, don’t say that!” the Host shuddered in horror at such a grievous accusation.

This comic relief stood in stark contrast to the intense stories told on the body of the show. Plots ranged from adaptations of classic Poe stories to noir-style murder mysteries similar to those then airing on other mystery shows like Suspense. Death, violence, murder, revenge, and retribution were constant themes. Some stories hinted at a supernatural element, which was usually explained away, but not always. The violence often got bloody, and could be just as gory as what EC was later criticized for doing in print. For instance, one episode opened with a reporter discovering the corpse of a sculptor who has cut off the heads of his cats and slit his own throat from ear to ear. Later in the episode we learn that it is an expression of remorse for beheading his unfaithful wife and taking her head to her lover in a box.

Inner Sanctum assembled the elements that would inform the early comic book horror formula associated with EC, using comic relief and graphic violence to frame traditional horror tales and modern noir mystery. In the next installment I’ll carry this story forward to the dawn of the horror comic.

Next: The First Horror Comics: Eerie and Others.