Over the weekend Tim Marchman of The Wall Street Journal published a piece on the state of the comic book industry, “Worst Comic Book Ever! While superheroes dominate the box office, the medium that birthed them has moved on.” while doing a review of Christopher Irving’s book Leaping Tall Buildings. The article’s main point–that the success of superhero movies is outpacing the sales of comic books–is sound. However the article’s explanation for this trend is marred by errors of detail and superficial analysis. I’m not sure whether some of these ultimately come from Marchman or Irving, but I’ll comment on a few here and propose a counter-thesis to the one Marchman advances.

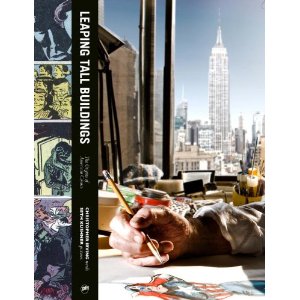

Leaping Tall Buildings: The Origins of American Comics

First, Marchman’s article contrasts today’s sales figures with those of “hot issues” of Spider-Man and X-Men from twenty years ago, which he characterizes as “the comic industry’s brief Dutch-tulip phase,” a reference to a 17th-century economic bubble that collapsed. Actually the comic industry’s sales peak came in the late 1930s and early 1940s before wartime paper rations took their toll. At that time top characters like Captain Marvel and Superman sold in the millions on a monthly basis, not just during “hot issue” spikes. By the 1992 time frame Marchman is talking about, after decades of inflation and changing distribution patterns, sales were already so far in decline that the industry had begun resorting to gimmicks to inflate sales demand, like giving characters new costumes, killing off characters, resurrecting characters, and issuing alternate covers. This trend was aided by uninformed media coverage which overhyped the investment potential of so-called “hot issues” like the “Death of Superman” story arc. So many copies of this lame story were printed that today you can buy a copy of Superman Volume 2 Number 75 on eBay for less than $10. Any long-term collector could have told you that would happen in 1992 (and many of us did). Marchman’s article seems to reflect a short-term perspective on the industry.

This short-term perspective also mars his commentary on the historical influence of various creators. After a one-sided summary of Siegel and Shuster’s relations with DC and Kirby’s relations with Marvel, he launches into an aside advocating “Alan Moore, the influential British writer who more or less revitalized DC Comics in the 1980s.” No, Moore did not “more or less revitalize DC Comics in the 1980s.” Marv Wolfman, George Perez, Frank Miller, and John Byrne were far more significant contributors to DC’s revival in the 80s, building on a foundation people like Dick Giordano, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil had laid in the 60s and 70s. Moore’s main contribution was attracting increased critical attention to the industry, but his titles were not nearly as popular or influential in stimulating sales and creative direction as Wolfman and Perez’ work on New Teen Titans and Crisis on Infinite Earths, Miller’s Batman, or Byrne’s Superman.

The gist of Marchman’s article seems to be advancing a thesis that the decline of industry sales stems from industry leaders relying on established formulas (or as Marchman puts it, again dating the range of his perspective, “sequels to comics that came out when New York Mets announcer Keith Hernandez was a perennial MVP candidate”) rather than following the lead of creators like Moore, Chris Ware, Robert Kirkman, and others more suited to Marchman’s tastes. Specifically, Marchman blames “Brian Michael Bendis, Joe Quesada, Grant Morrison, and Dan DiDio” as “the men most responsible for the failure of the big publishers to take advantage of the public’s obvious fascination with men in capes.”

This theory has a few problems. For one thing, it assumes that sales declines are entirely due to creative forces, as if economic forces like the rising cost of paper have played no role in sales trends.

It also assumes that the industry leaders Marchman blames have been reliant on traditional formulas. But for instance, I think many of us who have been reading comics since before Keith Hernandez was MVP (that’d be 1979 for non-baseball fans) would take issue with the implication that Joe Quesada’s Marvel is the same as the Lee-Kirby Marvel or even Jim Shooter’s Marvel. Likewise it’s a bit of a leap to equate Grant Morrison’s Batman with Denny O’Neil’s or Frank Miller’s, as Marchman’s theory would seemingly imply.

Marchman further assumes that the general public shares a taste for the type of avant-garde writers he likes. I submit that in fact the rise of these types of avant-garde writers is the biggest creative barrier to the industry reconnecting with the traditional blue-collar base that was responsible for millions of monthly sales in the 1940s. The mass market is a family market, not an avant-garde market. There is a place for avant-garde comics, but the notion that more products like Watchmen will propel the industry to mass commercial success is misguided.

This last point gets at the final problem with Marchman’s thesis that I’ll touch on. As the mediocre box office performance of Watchmen illustrates, the commercial success of comic book films is not being fueled by independent-oriented creators going off on avant-garde tangents, and it stands to reason that if this type of story isn’t selling movies, it’s not going to boost comic sales, either. The most successful film franchises like Batman, Spider-Man, Iron Man, and X-Men have stuck to popular storylines and have found success by satisfying a long-standing audience demand to see these stories brought to life on the big screen. I submit that the industry will find commercial success in mining historic successes and adapting them to stimulate creativity in new contexts, rather than in sweeping away decades of continuity in an effort to re-invent the wheel. In my opinion comic books need to get back to their roots if the industry is going to blossom again, instead of going off on an avant-garde branch and then cutting it off from the tree.