(This article was originally presented in Ditkomania # 76. It has been revised for this presentation.)

I’ve found you have to look back at the old things and see them in a new light.

–John Coltrane, interview, Down Beat magazine, 1966

Almost a half-century ago, during the pivotal year of 1962, Steve Ditko, in conjunction with Stan Lee, broke the boundaries of the standardized costumed-hero conventions.

It was then that Peter Parker was introduced to the comic book world. He was atypical in many respects: a teenager as a leading character was practically unheard of, let alone Ditko’s version, an awkward looking kid, with slouched shoulders and a forlorn look. Though transformed by super powers, he did not instantly transform into a heroic pillar; nor did he gravitate toward some moral high ground. Parker’s adolescent life was a crucial element of the strip and another deviation from comic book platitudes. Ditko invested the character with a rich setting and a diverse cast to play off of: a home life with his Aunt May in Queens, NY; relationships with fellow students in High School; a job as freelance photographer for the Daily Bugle and an ongoing romance with Secretary Betty Brant. Unlike other heroes, he was feared and condemned by the public for his actions as Spider-Man. At times, he questioned both his objectives and his sanity. This was a far cry from the beloved do-gooders as exemplified by Superman. Some of the ideas were clearly that of Stan Lee, who edited, co-plotted and dialogued all the stories, but Ditko’s input was invaluable from the beginning, and, in less than three years he would take complete control over the plotting. The strip’s progression reached a crescendo in the three part story featured in Amazing Spider-Man #’s 31-33.

The story opens with Peter busily preparing for college, but his world quickly falls apart. Aunt May blacks out and is taken to a hospital, where she is found to be gravely ill; this weighs heavily on Peter who tries unsuccessfully to concentrate on his studies. Peter is further traumatized when he discovers that her condition is the result of an earlier transfusion of his blood, never thinking that the spider bite that gave him extraordinary abilities would be detrimental to others. As doctors explore ways to treat her unidentified condition, they believe that an experimental drug, ISO-36, may offer a possible cure. A band of criminals, however, make off with the serum for their own purposes.

(In Alfred Hitchcock movies this is called the “MacGuffin.” According to Alfred Hitchcock: “the device, the gimmick, if you will, or the papers the spies are after. . .The only thing that really matters is that in the picture the plans, documents or secrets must seem to be of vital importance to the characters. To me, the narrator, they’re of no importance whatsoever.”)

Unknown to Spider-Man, his old foe, Dr. Octopus, is running the operation as the so-called “Master Planner.” Spider-Man desperately battles his henchman, eventually confronting Dr. Octopus, but as the two clash in his undersea sanctuary the tunnel becomes flooded, and the criminal is lost in the ensuing chaos. The cliffhanger ending in issue 32 (Jan 1966) leaves Spider-Man trapped beneath a ton of machinery, as water pours relentlessly and the serum remains tauntingly out of his reach.

The cover to The Amazing Spider-Man #33 (Feb 1966) concentrates on a somber scene: Spider-Man is positioned directly in the center, caught under a massive steel structure. His pinned figure is framed by cascading water in front of him, which also drips down his face, hands and shoulder, comprising the only visible parts of his body. Although his eyes cannot be seen, the reader is drawn in by the overwhelming sense of helplessness and desperation, evoking sympathy for the characters plight. Colorist Stan Goldberg’s palette of dreary grays and murky blues intensify the bleak atmosphere.

Inside, the momentum builds. In a stunning five page tour-de-force, Ditko orchestrates one of the most dramatic sequences in comic’s history.

Aptly titled “The Final Chapter”, the splash page opens with four small, consecutive panels that succinctly update the storyline. The fifth, large panel returns to the present situation, using an establishing shot that echoes both the cover scene and the final panel from the previous issue, although here Spider-Man’s head is lowered, emphasizing his demoralized state.

With the grace of a cinematographer, Ditko guides the viewer’s eye on the following four pages, deftly weaving from long shots to close-ups, as the panels grow in relation to the heroes’ emotional state.

Page two consists of seven panels, depicting Spider-Man’s mood as it shifts perceptibly from futility to tenacity, enforced by ghostly visions of his Aunt May and Uncle Ben (referencing the character’s origin story and the relative he failed to save from a criminals fatal bullet) The last panel centers on the hero, his fists clenched, indicating his growing determination.

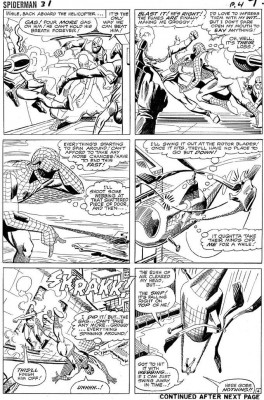

The tension escalates; page three showcases six panels that expand in dimension from tier to tier, as Spider-Man slowly gains headway, his arms straightening and his torso and leg revealed.

Page four includes three horizontal panels of equal dimensions; one showing the ceiling beginning to crack from the growing water pressure, the second two of Spider-Man resisting the pain and lifting the crushing tonnage. The fourth panel encompasses the remaining 2/3 of the page, a medium shot of Spider-Man finally on his knees, culminating on the fifth page, a single image of Spider-Man lifting the weight off of him; triumphant against overwhelming adversity. Ditko’s analogy was clear: Peter Parker was finally able to lift the “weight” of guilt that had haunted him since his Uncle’s murder. The teenager had come full circle, from confused youth to responsible adult, atoning for the mistakes of the past.

In the pages of a simple 12 cent comic book, Steve Ditko touched on themes that resonated with his audience. The burden of responsibility, and the often monumental effort to survive in a world where the odds are stacked heavily against you, addressed more than make-believe heroics. In terms of both narrative development and emotional appeal, Amazing Spider-Man # 33 was the culmination of the Lee-Ditko run. Even though Ditko plotted this story himself, as he had been doing for many issues, Lee performed his duties with craft and intelligence, and his language captured the dramatic tension expressed in Ditko’s pictures.

There was another point to be made, though. Spider-Man’s victory was achieved at a cost. The strain he put on his leg leaves him with a clearly visible limp. Obstacles remained in his path, including a flooded underground passageway and the remains of the Master Planner’s gang. Wounded, delirious, in a state of frenzy, Spider-Man throws punches unrelentingly, until, on the verge of collapse, he finally comprehends that the fight is over. Ditko conveys the sense of a flesh and blood man underneath the costume. In a rare moment Ditko offers a jarringly different result from the ordinary superhero confrontation with no repercussions.

Spider-Man delivers the serum to Dr. Curt Connors, his scientist friend who appeared previously as the Lizard. Ditko again strays from the obvious. Instead of using the character as a villain, he places him in a normal setting. Connors analyzes the serum and finds it compatible with Aunt May’s blood. After taking the serum to the hospital, Spider-Man returns to the crime scene to photograph the Master Planner’s men, who are being taken into custody.

When Peter arrives at the Daily Bugle to sell his pictures, Betty Brant notices that Peter is injured. As Peter turns to face Betty, she is taken aback by the bruises and cuts he sustained from his skirmish. While Comics Code restrictions did not permit Ditko to depict anything of a more graphic nature, the point was made. With grim determination Peter lays out his occupational risks to Betty: “I’m not complaining, and I’m not quitting my job either.” These words may have come straight from Ditko’s handwritten notes to Lee. This was a mature Peter Parker, set free of the doubts and fears that plagued his adolescent years. Influenced by Ayn Rand’s Objectivist beliefs, it was how Ditko saw a hero: supremely confident and adhering to his own principles.

Peter does not allow Jameson to take advantage of him either, demanding proper compensation for his work. The situation mirrored the freelancer/editor status of Ditko and Lee. Earlier in the year Ditko gave Lee an ultimatum, not for money, but for fair credit as story plotter on Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. He received it beginning in Amazing Spider-Man # 25 (Jun 1965), but, like the character he crafted, it would not come without consequences.

According to Ditko, Lee refused to speak to him afterwards. [“Then, at some point before issue # 25 (where I am publicly credited with plotting Spider-Man and Dr. Strange), Stan chose to break-off communicating with me.”–Steve Ditko, “A Mini-History, The Green Goblin”, The Comics, Vol 12, No 7 July 2001] Production manager Sol Brodsky was the intermediary between the two: taking the penciled pages, giving them to Lee to dialogue, then to either Artie Simek or Sam Rosen to be lettered, and back to Ditko to ink. In this awkward situation both men lacked total control, and the creative rift between Lee and Ditko would soon lead to a parting of the ways.

Returning to the hospital, Peter is greeted with the news that Aunt May will recover. In a moving panel, Peter looks down at his Aunt with satisfaction as she slumbers contentedly. Ditko portrayed May Parker with lines and wrinkles befitting an elderly woman, adding a degree of authenticity to the character which was eliminated when he left the strip.

Ditko ends the story with perfect symmetry. In four consecutive vertical panels the doctor draws down the blinds in Aunt May’s hospital room as he observes Peter limping away below. May’s face is in the foreground, the shadows of the shade slowly covering her face. The Doctor thinks:

“Too bad someone like HIM can’t be an idol for teenagers to imitate…instead of some mysterious, unknown thrill-seeker like—SPIDER-MAN!!”

Although Ditko continued on Spider-Man for five issues, they seemed little more than an afterthought. The writing was on the wall, as Ditko grew increasingly disillusioned with the Marvel method, in which Stan Lee supervised the production process.

As Editor, Lee was the final arbitrator, and could not only alter thematic aspects of the story line, or add a false sense of characterization, but could also modify the visuals, in a way that was never intended. In the end, it was inevitable that Ditko, who felt the need to find his own independent voice, would opt out of the relationship. As a commercial product, The Amazing Spider-Man remained a top selling comic book, and Publisher Martin Goodman, who owned the property, made sure it remained that way under Lee’s guidance.

Creatively, though, Steve Ditko’s contributions could not be duplicated by any other artist. Like John Coltrane’s My Favorite Things, Steve Ditko reached a pinnacle with his storytelling in Amazing Spider-Man # 33. Over forty years later the story stands up to repeated readings, resonating with intensity and personal expression–a testament to the unique individuality that defines the work of Steve Ditko.

With special thanks to Frank Mastropaolo for his editing skills and observations.

EDITOR’S RECOMMENDATION: For more of Nick’s nostalgic knowledge, visit his blog Marvely Mysteries and Comics Minutiae at http://nick-caputo.blogspot.com/

Thanks, Nick, for a great in-depth analysis of a classic storyline! The lifting sequence has actually meant a lot to me personally because it has inspired me in some tough situations. It is definitely a highlight of Ditko’s work on Spider-Man.

Hi Roy,

Thanks for the kind words. I’ve often thought of the story as well on a personal level. Not many comic book stories resonate so strongly, but Ditko brought an emotional punch to so much of his work.

If anyone found this interesting, please take a look at my Blog, which often features Ditko content, but concentrates on many areas of comics and comic art.

http://nick-caputo.blogspot.com/

Thanks for reminding us of the link to your blog! I added a note at the bottom of the article to make sure people see that. You’re also in our sidebar short list of recommended links. Great stuff!

You guys are posting at 6Am and 8 AM?

We put the “fanatic” in “fan”!–mostly because it counts more if you spell it that way in Scrabble!

Roy,

Thanks for the publicity, its greatly appreciated.

I remember reading those issues and eagerly awaiting the next. I was shocked by Ditko’s departure and while I continued to buy the book it was never the same. I think if #33 had been the last issue of Spider-Man the thirty plus issue run would still be considered some of the best super-hero stories ever published.

Steve,

I was too young to be shocked by Ditko’s departure, since the first ASM I ever saw on the stands was #39, but at the same time I was reading Marvel Tales, which reprinted the early Lee -Ditko run, and my older brother John had most of the back issues. I was of the age when Spider-Man by Lee and Romita grabbed me, and it was my favorite comic book. Having said that, the earlier work of Ditko resonated, and continues to resonate for me. As fine a craftsman as Romita is, there is no denying the depth and originality that Ditko brought to the strip.